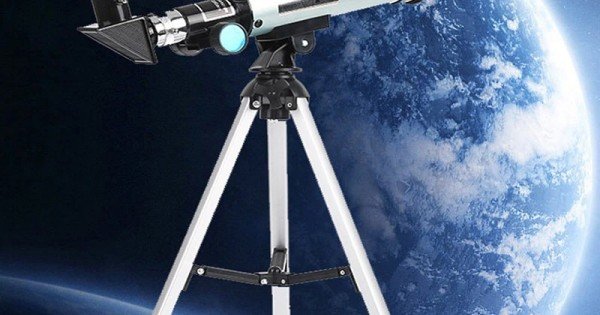

F36050 Telescope Optical Glass And Metal Tube

I remember the first time I truly saw the moon. Not the blurry, indistinct smudge you might catch on a bright night, but a real, crater-pocked, magnificent orb. I was maybe ten, staying at my grandparents' place in the countryside. My grandpa, bless his tinkering soul, had this old, slightly battered telescope. It wasn't fancy, definitely not one of those sleek, computerized marvels you see advertised today. This thing looked like it belonged in a steampunk inventor's workshop – lots of polished brass, a long, sturdy metal tube, and a couple of chunky eyepieces. But oh, the magic it held!

He’d set it up in the backyard, the air crisp and smelling of pine needles and damp earth. He pointed it at the moon, and I, with my young eyes still accustomed to terrestrial views, peered in. And there it was. Clear as day. Mountains casting shadows. Seas (they looked like seas to me then, anyway) etched into its surface. It was like suddenly being given a new pair of eyes, eyes that could pierce the veil of distance and reveal the secrets of the cosmos. That night, the universe cracked open a little for me. And it all started with a simple tube of metal and a piece of glass.

Which, coincidentally, brings me to the rather understated yet profoundly important components of any decent telescope: the optical glass and the metal tube. You might think it's all about the fancy mounts and the digital readouts, but at its core, a telescope is a surprisingly elegant marriage of these two fundamental elements. Let's dive in, shall we?

The Star of the Show: Optical Glass

When we talk about the "eyes" of a telescope, we're talking about the lenses and mirrors. These aren't just any old pieces of glass. Nope. This is special-sauce glass, meticulously crafted and precisely shaped to bend and focus light. Think of it like this: light from distant stars and planets is, well, distant. It's faint and spread out. The job of that precious optical glass is to gather as much of that faint light as possible and then, with incredible accuracy, bring it to a single point so our eyes can see it. Pretty neat, huh?

There are two main players in the optical glass game: refractors and reflectors. Refractors use lenses, like your eyeglasses, to bend light. They're the classic "telescope" look – that long tube with a big lens at the front. They tend to be sharp and provide great color contrast, but for really large telescopes, they can get super expensive and heavy. Trying to make a massive lens perfectly clear and free of distortion is an art form that requires insane precision and a whole lot of patience (and probably a bit of magic). Plus, at a certain size, light starts to get absorbed by the glass itself, which is a bit of a bummer.

Reflectors, on the other hand, use mirrors. These usually have a primary mirror at the back of the tube that collects light and bounces it towards a secondary mirror, which then directs it to your eyepiece. This is where you get those big, beefy telescope designs. Mirrors are generally easier and cheaper to make in larger sizes than lenses, which is why most of the giant telescopes you see at observatories are reflectors. They're like giant satellite dishes, but for light instead of radio waves. The craftsmanship involved in making a perfectly parabolic mirror, so that every ray of light hits the right spot, is absolutely mind-blowing.

And let's not forget the coatings! Oh, the coatings. These aren't just for show. They're thin layers of various materials applied to the glass surfaces to reduce reflections and maximize the amount of light that actually gets through to your eye. Think of it as giving the glass a super-slick, anti-glare finish. Without good coatings, a lot of that precious starlight would just bounce off the surfaces and get lost, leaving you with a dim, washed-out view. It’s the difference between looking through a dirty window and a crystal-clear one.

The Unsung Hero: The Metal Tube

Now, while the glass is doing all the fancy light-bending, what about that trusty metal tube? It might seem like just a container, but it's so much more than that. The tube, often made from aluminum, steel, or even carbon fiber these days, has a crucial job: to hold everything in alignment and keep stray light out. And believe me, stray light is the enemy of a good astronomical view. Imagine trying to read a book in a brightly lit room; it's hard to focus, right? The same principle applies to telescopes. The tube acts like a blackout curtain, preventing ambient light from sneaking in and diluting the faint light from the stars.

Alignment is also key. Those lenses or mirrors need to be positioned perfectly relative to each other. Even a tiny wobble or misalignment can throw off the entire image. The metal tube provides a rigid, stable structure that keeps everything locked in place, no matter how much you might jostle the telescope (which, let's be honest, happens). It's the backbone that supports the delicate optical components.

And then there's thermal stability. Metal, especially certain alloys, expands and contracts with temperature changes. While this might sound like a bad thing, clever telescope designers account for this. The tube needs to be robust enough to withstand these changes without warping or shifting the optics. In some higher-end telescopes, you’ll even find tubes made of materials like carbon fiber, which are chosen for their very low expansion rate, meaning the telescope's performance stays consistent even as the temperature fluctuates. It's about maintaining that perfect alignment through thick and thin… or rather, through hot and cold.

The inside of the tube is usually coated in a matte black finish. Why? You guessed it: to absorb any stray light that manages to get in. This prevents internal reflections from bouncing around and creating fuzzy or ghosting images. It’s like the velvet lining of a jewelry box, making the precious contents stand out. Without that matte black interior, even the best optics would be fighting a losing battle against internal glare.

The F36050: A Case Study (Sort Of)

Now, let's talk about a specific example, the rather intriguingly named F36050 telescope. The name itself sounds a bit like a secret agent or a codename for a cutting-edge piece of tech, doesn't it? In reality, the 'F36050' often refers to a common type of entry-level astronomical telescope, typically a refractor. The 'F360' likely refers to the focal length (360mm), and the '50' to the diameter of the objective lens (50mm). This makes it a relatively compact telescope, often favored by beginners or those looking for something portable.

For a telescope like the F36050, the optical glass would likely be a standard achromatic refractor lens. This means it’s made of two different types of glass cemented together to reduce chromatic aberration – that annoying rainbow effect you can sometimes see around bright objects, especially on lower-quality optics. It's a good compromise for an affordable scope, giving you a decent view without breaking the bank. It’s not going to show you the rings of Saturn in stunning detail like a much larger, more sophisticated telescope, but it will show you the moon’s craters, Jupiter’s moons, and maybe even the fuzzy glow of a distant nebula. And for someone just starting out, that’s a gateway to a whole new world.

The metal tube for a telescope like this is typically made from aluminum. It’s lightweight, relatively strong, and easy to manufacture. The diameter of the tube will be dictated by the 50mm objective lens, and it will be long enough to accommodate the 360mm focal length and the eyepiece. For an entry-level scope, the manufacturing tolerances might not be as extreme as in a professional instrument, but for its intended purpose – introducing people to the wonders of the night sky – it’s perfectly adequate.

The beauty of the F36050 (and telescopes like it) is its accessibility. It’s a tangible link to the cosmos for a relatively low price. It embodies that fundamental principle: take some carefully crafted optical glass, house it in a sturdy, light-blocking metal tube, and suddenly, you have the power to explore the universe from your backyard. It's a testament to human ingenuity and our innate curiosity about what lies beyond.

More Than Just Parts: The Synergy

What’s truly fascinating is how these two components – the optical glass and the metal tube – work in perfect synergy. One can’t function without the other. Imagine having the most perfectly ground lens in the world, but if you just held it up in the air, light would bounce around all over the place, and you'd get a blurry mess. The tube provides the structure, the stability, and the light control that allows the optics to do their job effectively. Conversely, even the most robust metal tube is useless without the light-gathering and focusing power of the optical glass.

It’s a relationship of mutual dependence, a partnership that has been crucial in our understanding of the universe for centuries. From Galileo’s rudimentary refractor to the Hubble Space Telescope (which, despite its complexity, still relies on these fundamental principles), the combination of precise optics and a protective housing has been the key to unlocking celestial secrets.

When you look through a telescope, you’re not just seeing stars. You're seeing the culmination of countless hours of design, manufacturing, and testing. You’re experiencing the result of highly skilled artisans shaping glass with incredible precision and engineers designing structures that can withstand the rigors of both terrestrial and celestial environments. It’s a beautiful, often overlooked, collaboration.

So, the next time you have the chance to look through a telescope, take a moment to appreciate not just the breathtaking views, but the humble yet vital role played by the optical glass and the metal tube. They are the silent guardians of our cosmic visions, the unsung heroes that allow us to reach for the stars. And who knows, maybe that glimpse of a faraway world will spark a lifelong fascination, just like it did for me on that crisp countryside night, gazing at the moon through a decidedly un-steampunk, but undeniably magical, old telescope.